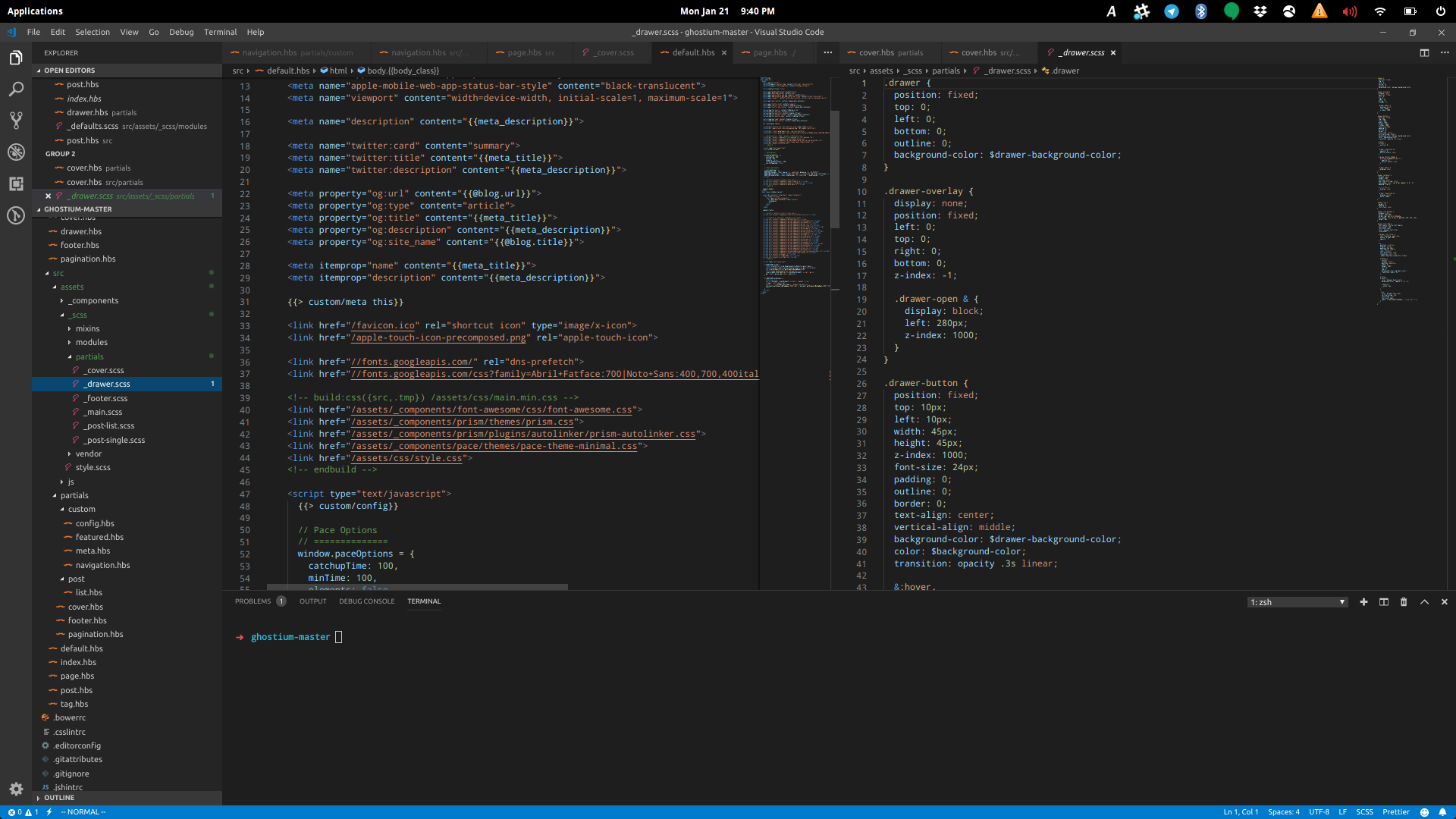

Developer Friendly Software

It’s ready now, you know it. You’ve spent a lot of time writing this masterpiece. Your finest work thus far. It’s time for other people on your team to know about this library / software you just made. You brace yourself for the positive feedback you’re going to get, oh fo’ sho'!

“How do I use this?”, “Why did you do that?”, “Oh we already have a library for that”…

This wasn’t the great reveal you were expecting.

So, what went wrong?

Couple of things come to mind:

- You worked alone for too long without code review

- Trying to reinvent the wheel

- Not following standards

- Did not give enough thought into API design

1. Work as a team, you must

Rarely anyone works solo anymore. Even as the sole developer in your company, you’ll always have code connecting to other services, connecting to your own services. Or just code that eventually someone needs to see.

I am a strong believer of regular pair programming - it forces you to think like another developer. It doesn’t just reduce bugs, it also makes sure that other developers on your team understand what you were trying to do.

“Pair programmers: Keep each other on task. Brainstorm refinements to the system. Clarify ideas. Take initiative when their partner is stuck, thus lowering frustration. Hold each other accountable to the team’s practices. Pairing” - Kent Beck

Basic “good programming” paradigm are basic for a reason - it makes developers’ life easy. Have good variables, have useful comments, prioritize code comprehension over performance. These things become apparent as you pair program.

2. Can you build a better wheel by yourself?

It’s not always wrong to reinvent the wheel. Sometimes it can be very beneficial to do so, especially if:

- The library available is overly bloated and heavy

- You’re practicing

- Existing libraries have outdated dependencies

More often than not, we as developers tend to think that we know best. That we’re going to make it so much more easier to use. Our new version will have all the bells and whistles that anyone would ever need.

But we are not artists in the traditional sense - we don’t need our own voice in code. Good code is code that everybody understands and able to use with ease. Imitating someone else’s voice can be a good thing!

Rewriting a function or a library will lead to bugs that other people might have already solved. New code are error prone, it hasn’t seen battle enough. It takes time to document everything well.

New functions also mean someone will have to rewrite their code to fit your new fancy library.

There certainly are situations in which code reuse is the best option, but it is not always the best choice. Reuse in software development is certainly different from the reuse of bricks when building a wall - Dimitry C.

But of course, square wheels need to be reinvented

Of course I am not against innovation. There are many times a newer software improved the tech ecosystem by leaps and bounds, examples like Git that replaced SVN, Vue.js replaces jQuery, Typescript replaces ES6, Lodash replaces Underscore.

Notice that each new technology improves upon standards already established by the former. Remember, we as developers stand on the shoulders of giants before us. We don’t necessarily need to go down to fix the low level basics again.

3. Convention over configuration

Remember back when phone chargers were all different? When every phone had a slightly different port and different voltage for each brand? Then came the savior that is micro-USB that saved us all from Apple hell?

That my friend, is standards. Standards are the back bone of technology. Universal compatibility drives the web, internet and its’ protocols work on all OSes.

Good code has to adhere to some form of standards, and that means:

- Using proper server response code when appropriate, e.g. 500 only for server errors, 403 for unauthorized requests

- Accept common data formats such as JSON or YAML

- Format code similar to widely used style guides

- Follow framework recommendations for folder structures

“Bad programmers worry about the code. Good programmers worry about data structures and their relationships.” - Linus Torvalds

Standards make it that little bit easier to understand code and the flow of data within the software.

4. Better API Design

We’ve all seen code like these

let income = lib.calcPoints(4800, 0.1, 20, 50, 'single')

But what is 4800? What is the 0.1? What does single refer to? Does it really need 5 parameters? What does calcPoints() even mean?

Or what about this actual code for the aptly named programming language called Brainfuck.

++++++++[>++++[>++>+++>+++>+<<<<-]>+>+>->>+[<]<-]>>.>---.+++++++..+++.>>.<-.<.+++.------.--------.>>+.>++.

Design your code

Programmer does not mean you do not design, far from it. A programmer is a writer, a programmer write so that other programmers can understand. A compiler speaks to the computer, not you.

“Humans have powerful but limited cognitive capacity.” - Mike Bostock

As a writer, you design the words that will be seen. Having easy and clear understandable APIs makes it easy for you and others.

let income = calcIncome({

gross: 4800,

savingsPercent: 0.1,

taxPercent: 20,

credit: 50,

maritalStatus: 'single'

})

// Using destructing to accept object as parameter

calcIncome({gross, savingsPercent, taxPercent, credit, maritalStatus}) {

console.log(gross);

console.log(savingsPercent);

...

}

2 months after abandoning the project, you’ll still be able to immediately understand what is required to use the function, instead of having to jump to definition and re-read the function again to know what it needs.

Consistency is key

Remember that time you had to send a POST to get a a list of users? What about feeling like you had to jump over hoops to do parse an array?

Germane cognitive load is the processing, construction and automation of schemas, which is a pattern of thought or behavior that organizes categories of information and the relationships among them.

Germane cognitive load is a UX theory that utilizes a pattern or information that user’s already know, in order to make it easier for them to understand what we’re trying to convey through design.

For example: hamburger menu was at one point a very common and easy way for users to find the drawer for all the navigation. Everyone looked out for it whenever they couldn’t find where they wanted to navigate to.

Similarly, having consistent API endpoints can make it easy for any user of your library to guess what the function does without reading much documentation.

Lodash is a good example of a library that has consistent APIs.

var users = [

{ 'user': 'barney', 'active': true },

{ 'user': 'fred', 'active': false },

{ 'user': 'pebbles', 'active': false },

{ 'user': 'pollock', 'active': false }

];

_.findLastIndex(users, 'active');

// => 0

_.chunk(users, 2);

// => [[

// { 'user': 'barney', 'active': true },

// { 'user': 'fred','active': false },

// ],[

// { 'user': 'pebbles', 'active': false },

// { 'user': 'pollock', 'active': false}

// ]]

_.uniqBy([{ 'x': 1 }, { 'x': 2 }, { 'x': 1 }], 'x');

// => [{ 'x': 1 }, { 'x': 2 }]

3 different APIs with three different uses - but very similar input and output. Simple to use, does what is expected, and has great function name.

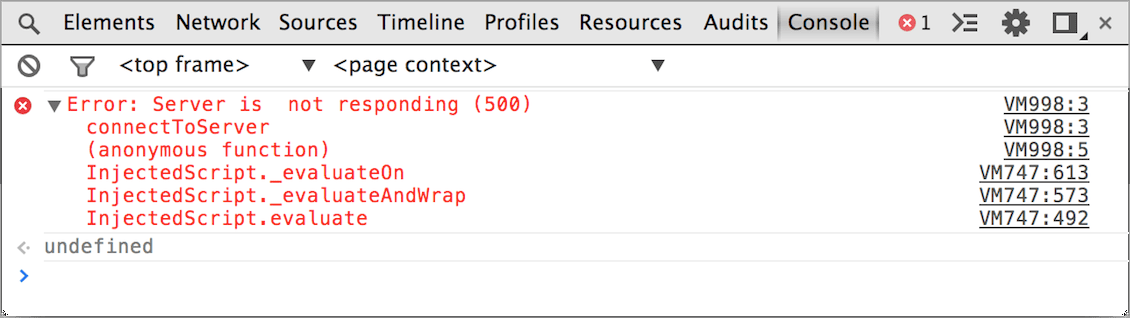

Throw better errors

Any seasoned programmer will tell you, bug fixing is probably the bread and butter of their work - it’s also the most hated part of their work. Having proper errors helps direct the developer to a ballpark area of what might be wrong. Was it external? Was it their fault?

The main difference between the error messages coming from library level and service/application level is debugging information. - Robert Vandenberg Huang

To start off,

- Handle errors properly when making HTTP calls.

- Handle timeouts when something is calculating for too long

- Incorrect or missing parameters

Chrome and Firefox at least comes with console logs that are color coded.

- Use console.log() for basic logging

- Use console.error() and console.warn() for eye-catching stuff

- Use console.group() and console.groupEnd() to group related messages and avoid clutter

- Use console.assert() to show conditional error messages

Summary

At this point, I feel like I’ve been just reiterating the same points over and over again. UX design and programming can be applied to each other. Developer are users too, and as such, can be treated to better and easier to read/use code.

I always believe that an easy-to-use library is always better than a powerful but difficult to use library. If I wanted performance, I would just write in assembly code.

Taking some time to consider the user’s perspective can go a long way to making better software, for developers and non-developers.

References

[1] https://www.thereformedprogrammer.net/what-makes-a-good-software-library/

[2] https://codeburst.io/writing-libraries-is-good-way-to-improve-your-development-skill-55b24384a120

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_load

[4] https://lodash.com/docs/4.17.11

[6] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/7505623/colors-in-javascript-console

[7] https://medium.com/@mbostock/what-makes-software-good-943557f8a488

[8] https://medium.com/@weblab_tech/pair-programming-guide-a76ca43ff389

[10] http://dimitri-on-software-development.blogspot.com/2009/12/disadvantages-of-code-reuse.html